What is Alpha-gal Syndrome?

The Mammalian Meat Allergy

What Is Alpha-gal Syndrome (AGS)?

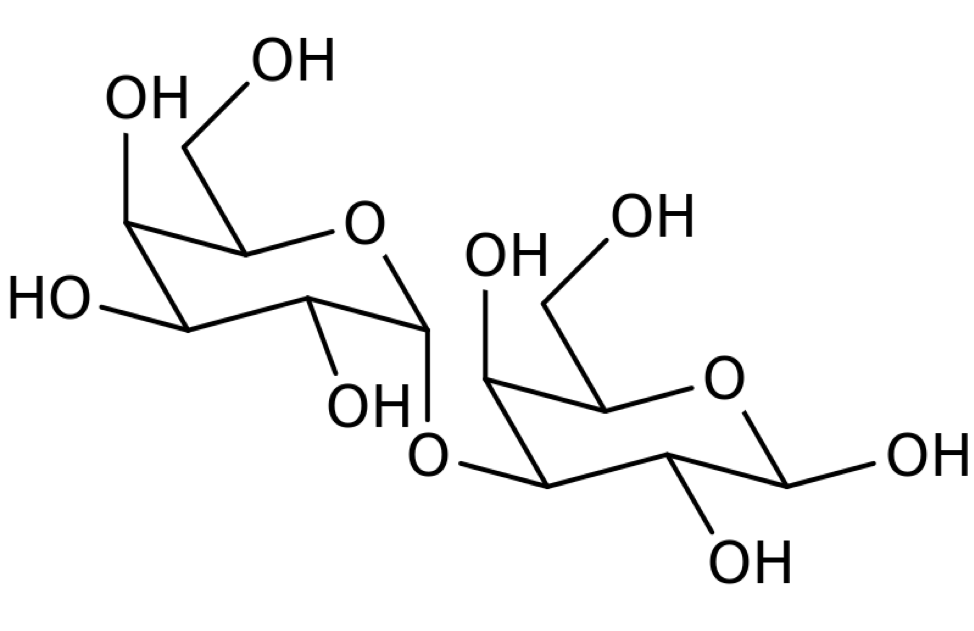

The term α-Gal syndrome describes a novel IgE-mediated immediate-type allergy to the disaccharide galactose-α-1,3-galactose (α-Gal). Its classification as a syndrome is proposed on the basis of its clinical relevance in three different fields of allergy: food, drugs, and tick bites.

Fischer, et al (24)

Alpha-gal syndrome (AGS)

also known as mammalian meat allergy, is an allergy involving an IgE antibody response to galactose-α-1,3-galactose (1). This sugar, commonly known as alpha-gal, is found in all mammals except for Old World monkeys, apes, and humans (99), as well as some other organisms. The onset of AGS is associated with tick bites (3).

Alpha-gal syndrome was first described in 2009 (1). It is poorly understood within the medical community because of its recent discovery and its varied and atypical presentation. Reactions to alpha-gal are often severe and sometimes fatal. They can be immediate, as with hypersensitivity reactions to injected drugs, or delayed by 2 to 10 hours or more, as is typical after consumption of mammalian meat (118). Delayed-onset reactions often occur in the middle of the night (1).

Alpha-gal allergic reactions can occur after exposure to:

- Mammalian meats, organs, and blood (57)

- Dairy products, gelatin, and other foods derived from mammals (57)

- Foods that contain mammalian byproducts (57)

- Drugs, medical products, personal care, household and other products with mammalian ingredients (57)

- Products containing carrageenan, which isn’t from a mammal, but which contains the alpha-gal epitope (54,57)

- Flounder eggs (26)

Symptoms→

Diagnosis→

Management→

Alpha-gal

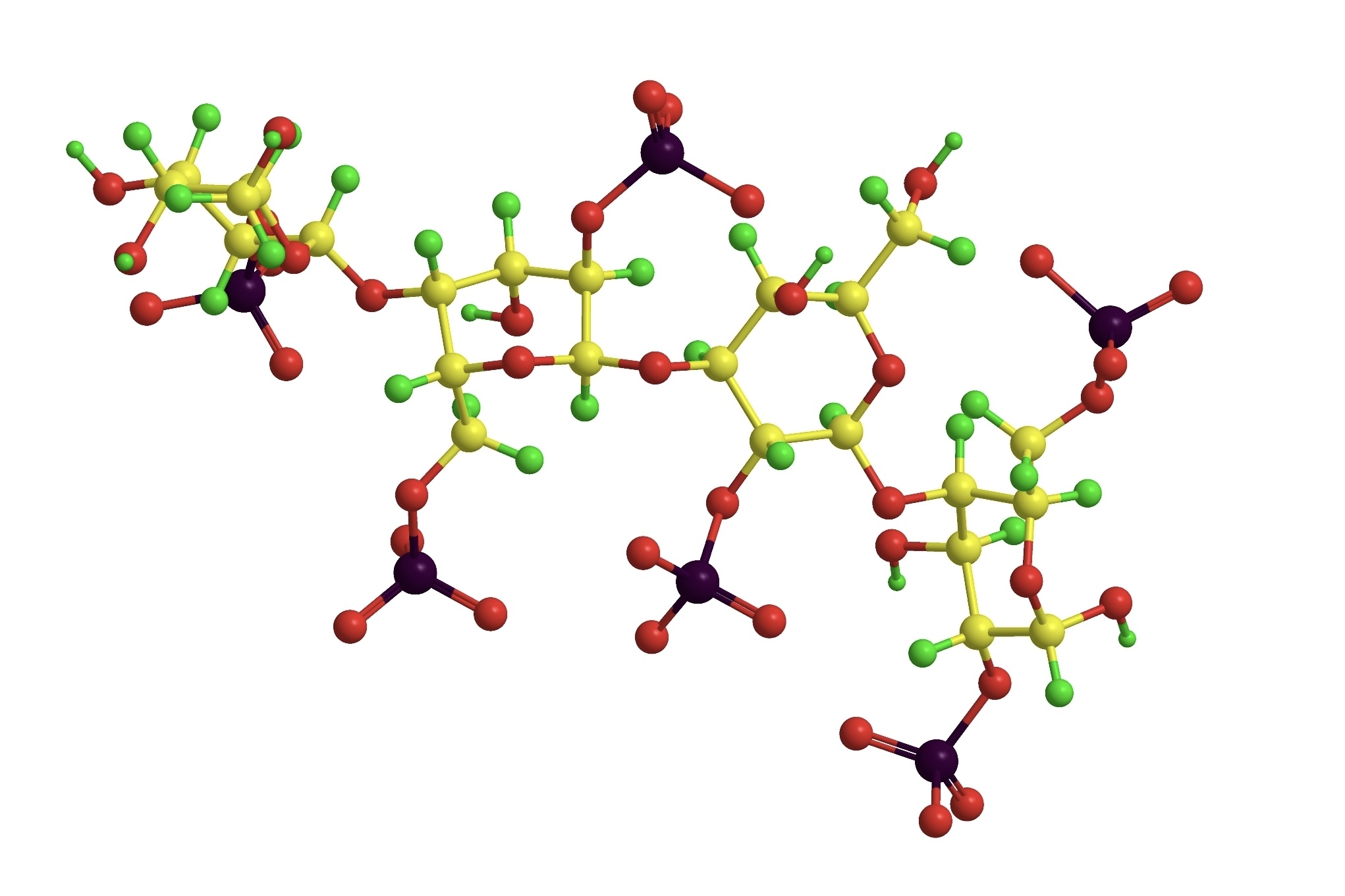

Galactose-α-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal or α-gal) is a disaccharide sugar.

- Alpha-gal is a common component of mammalian glycolipids and glycoproteins and is found in the cells, tissues, and fluids of all mammals except for Old World monkeys, apes, and humans (58,70,93,94,95,96,97).

- Some bacteria, protozoa (58), invertebrates (73), fungi (such as aspergillus) (73), and red algae (71) (including those used in the manufacture of carrageenan) (54), also express alpha-gal.

- Many viruses incorporate alpha-gal into the glycoproteins of their envelopes (58).

- Numerous human pathogens express alpha-gal (58).

- Most non-mammalian vertebrates do not normally express alpha-gal, although it is found in cobra venom (58, 72) and the eggs of some teleost fish (including flounder) and amphibians (26,58,74). There are other exceptions as well (58,75).

- Unlike proteins, alpha-gal is not denatured at normal cooking temperatures (70).

A Paradigm-Shifting Allergy

AGS differs from typical allergies in significant ways:

- AGS is associated with tick bites (3).

- It is one of only two carbohydrate allergies that cause life-threatening reactions (4).

- Lipids, in addition to proteins, are an important source of the allergen (100).

- Its presentation is atypical and includes delayed-onset reactions that can occur 2-10 hours or more after exposure, often in the middle of the night (1,5,6).

- Reactions do not occur after every exposure or follow an obvious pattern. This lack of consistency has been described as “almost a diagnostic hallmark” by experts (57).

- Co-factors such as alcohol consumption and exercise can dramatically impact the severity of reactions or whether they occur at all (22,23,57).

- In 3-20% of cases, patients report gastrointestinal symptoms alone, without other symptoms. Prior to diagnosis, many patients are misdiagnosed with IBS or other GI conditions (57).

- AGS is associated more with adults than children, and onset in adults and older children who previously tolerated red meat is common (57).

- Hunters, foresters, and other populations with high exposure to ticks are more at risk of developing AGS (57,59,69,98). In some regions, twenty times as many people living in rural areas may be sensitized than people living in nearby urban areas (98).

- The allergy component of AGS is only one dimension of a complex immune response that may have other health implications (7). Conditions tentatively linked to the alpha-gal immune response include some autoimmune diseases (7), arthritis (60), and atherosclerosis (79,80).

“Activity, alcohol consumption, and exercise can have profound influence on reactivity. Some patients appear to have reactions that require co-factors such that they can tolerate exposures in isolation; consistent with a diagnosis of co-factor dependent-AGS.” (57)

“Unlike more traditional food allergies where consumption of an allergen produces symptoms within minutes, AGS reactions typically occur 3-8 hours after eating. Thus many patients fail to consider food as a possible trigger and many healthcare providers do not routinely recognize the characteristic delay–both issues can prolong tie to reach a diagnosis.” (57)

“While GI complaints are not uncommon as part of an allergic reaction, 3-20% of patients with AGS report abdominal pain, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, or heartburn in isolation of cutaneous, cardiovascular or other signs/symptoms.” (57)

“…there are also patients who have episodes of abdominal pain without any skin involvement. Those cases are a problem because the possibility of food allergy is not obvious, and they can be severe… Other diagnoses that arise less commonly are arthritis and chronic pruritis. Distinguishing [AGS] from chronic hives can be challenging.” (6)

An Emerging Epidemic

A Growing Threat

As tick populations swell and their ranges expand (3,9,10,15) the number of people being diagnosed with alpha-gal syndrome is rising (8). Models suggest that this will continue (10,15).

- AGS is already a common allergy in some regions of the world, including the U.S. (11), where the number of diagnosed cases has risen from 12 in 2009 to over 34,000 in 2019 (63).

- The primary U.S. lab testing for alpha-gal IgE, ViraCor Eurofins, reported over 14,500 positive test results in a recent twelve-month period (81).

- In populations with high exposure to ticks, 15-35% of individuals can be sensitized to alpha-gal (57). Even for people without the clinical symptoms of AGS, alpha-gal sensitization could be a risk factor for coronary artery disease (79,80).

- In some areas, including much of the southeastern U.S., up to 3% of the population is estimated to have clinical AGS with anaphylactic reactions (57,61). The vast majority are undiagnosed or misdiagnosed with other illnesses.

- People in rural areas and others in frequent contact with ticks, including foresters, hunters (57,59), loggers, and people with outdoor hobbies (15) are especially at risk.

- AGS is the leading cause of adult-onset food allergy and anaphylaxis throughout the South and much of the eastern U.S. (12).

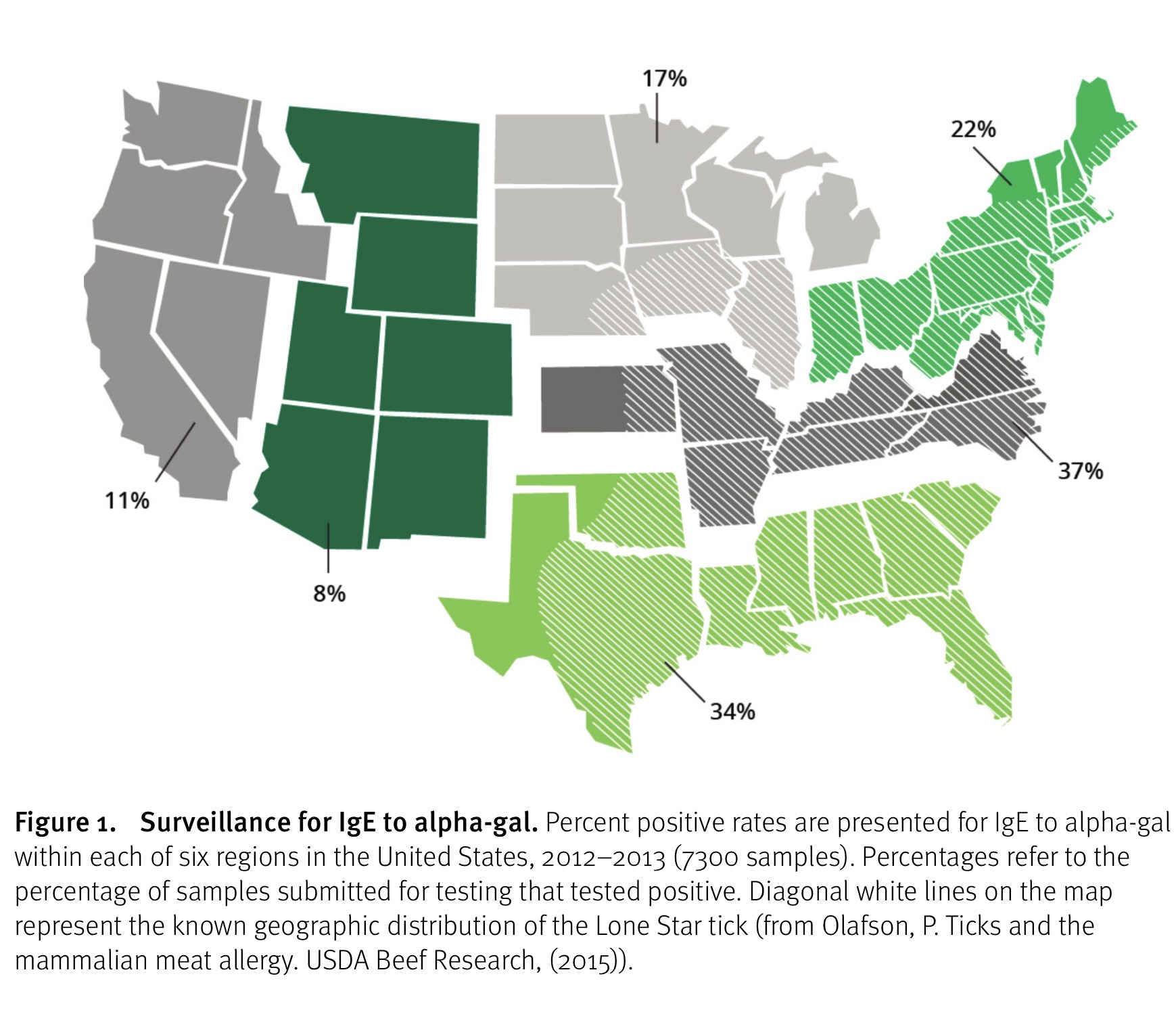

Source: Olafson, P. Ticks and the mammalian meat allergy. USDA Beef Research, (2015)

Source: Bianchi J, Walters A, Fitch ZW, Turek JW. Alpha-gal syndrome: Implications for cardiovascular disease. Global Cardiology Science and Practice. 2020 Feb 9;2019(3).

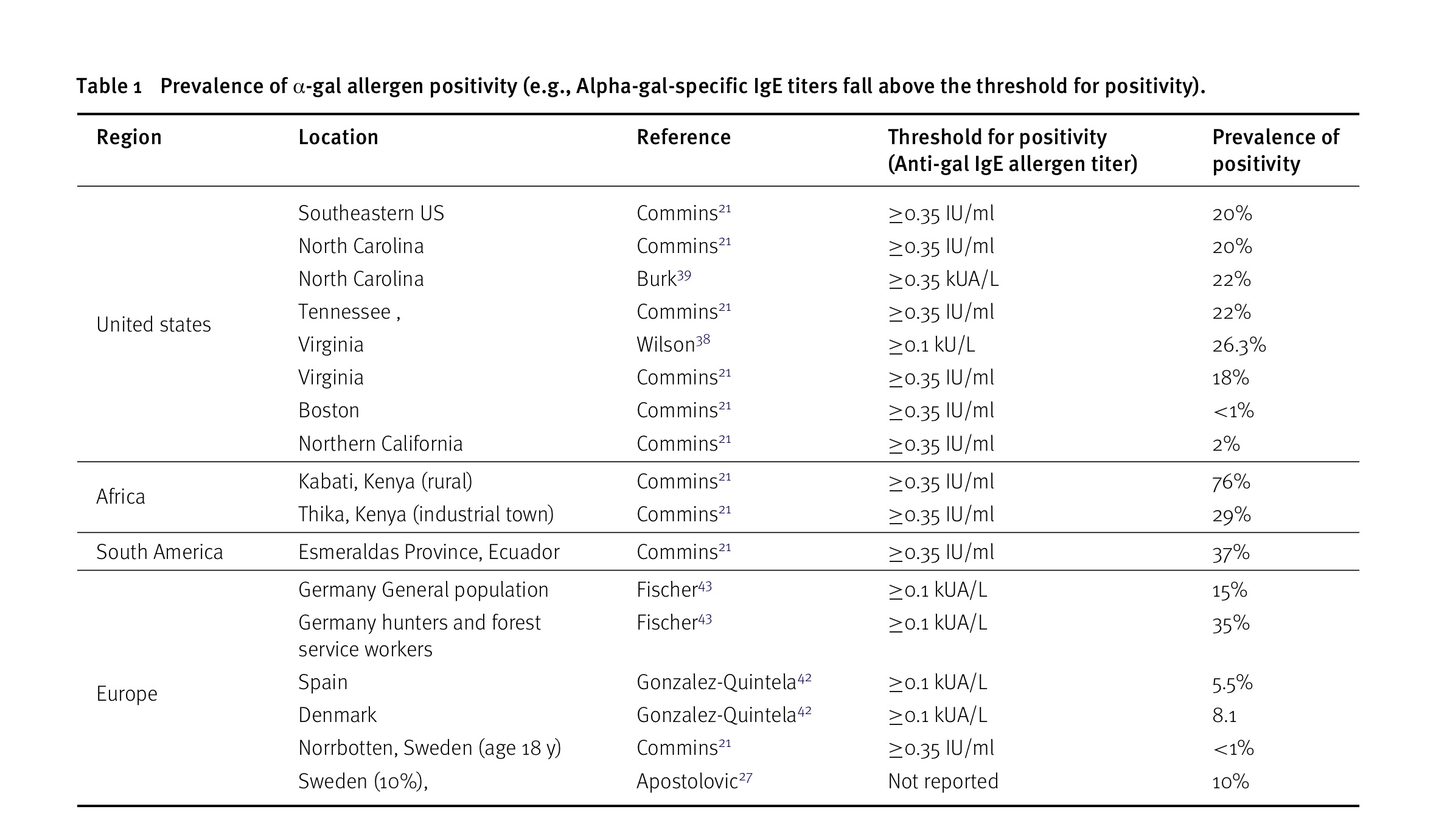

At a threshold for positivity of 0.35IU/ml, up to 9% of people sensitized to alpha-gal have clinical alpha-gal syndrome with anaphylactic reactions after eating mammalian meat or organs (59). At the lower threshold for positivity of 0.1IU/ml, as few as 1% of people sensitized to alpha-gal have clinical alpha-gal syndrome (57). In populations with high rates of infection with endoparasites, sensitization to alpha-gal may be more common but less associated with clinical symptoms (18).

“The reported prevalence of individuals in the United States with elevated allergen-specific titers of anti-gal IgE (i.e. allergen positive) has been reported to be in the range of 8% to 46%, with highest prevalence within the geographic distribution of the Lone Star tick. Similar prevalence rates have been reported in other regions around the world.”

“Children within the geographic distributions of certain ticks are projected to have allergen positive prevalence comparable to the adult population. As one might expect, hunters and forest service workers have been reported to have a prevalence that is more than twice that of the general population. It appears that the prevalence of AGS equates to 10% of the allergen-positive population. Thus, in the southeastern United States, approximately 3% of the general population exhibits anaphylaxis after consumption of mammalian meat.” (61)

A Leading Cause of Anaphylaxis

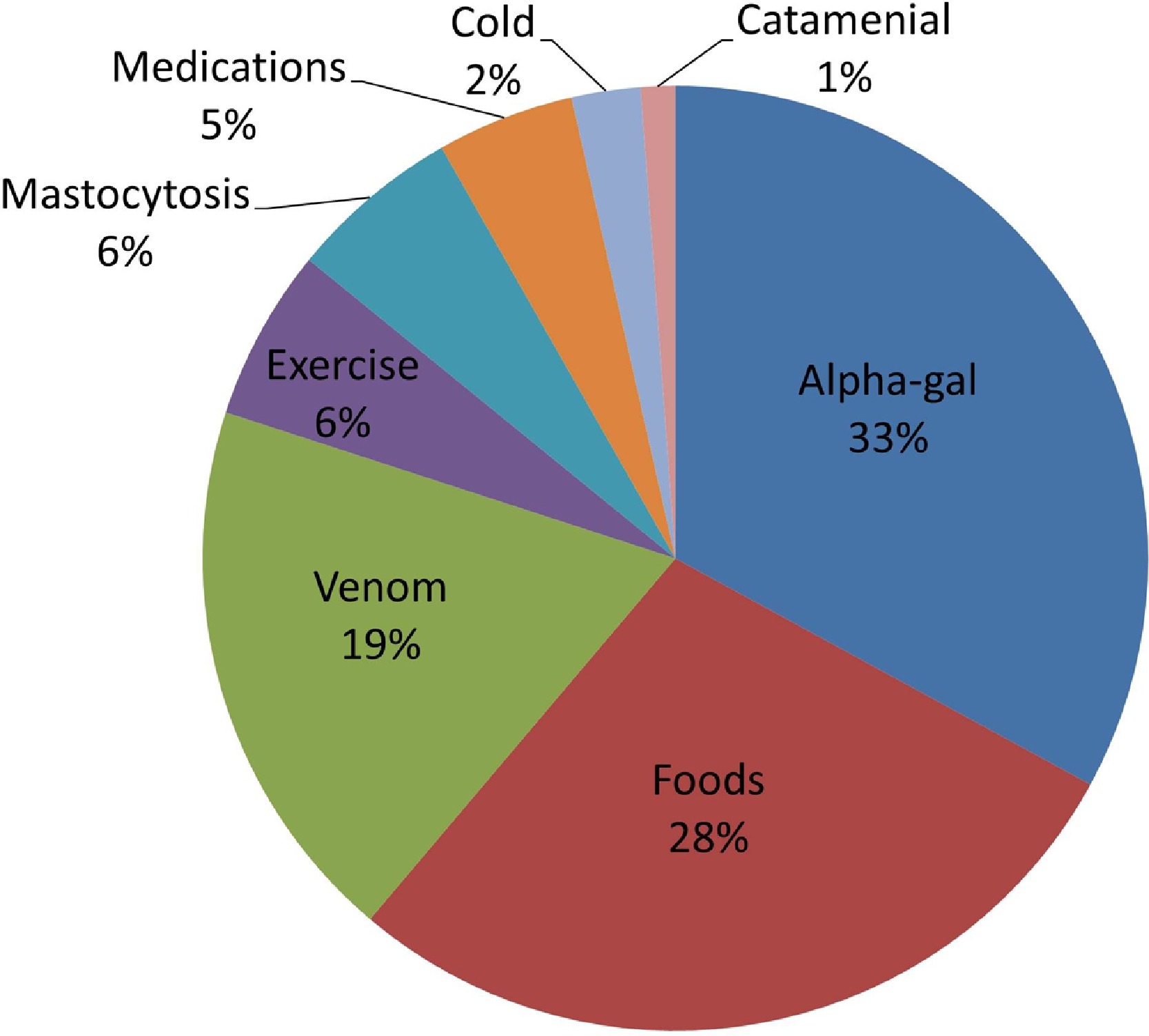

- Roughly 60% of people with AGS have anaphylactic reactions (24,78,87,88,89, 119) and 30-40% have cardiac and respiratory symptoms (90).

- In one recent study of anaphylaxis, AGS was found to be the number one trigger, accounting for 33% of cases with a definitive cause. The number two cause was all other food allergies combined at 28% (44).

- In the same study, recognition of AGS led to a reduction in the percentage of anaphylaxis cases without a definitive cause from 59% to 35% of total cases. (44)

- In a second study, nine percent of all patients referred with unexplained anaphylaxis were found to have AGS (62).

Figure 1. Etiologies of anaphylaxis based on proposed “definitive cause.” Alpha-gal, galactose-a-1,3-galactose.

Source: Pattanaik D, Lieberman P, Lieberman J, Pongdee T, Keene AT. The changing face of anaphylaxis in adults and adolescents. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2018 Nov 1;121(5):594-7.

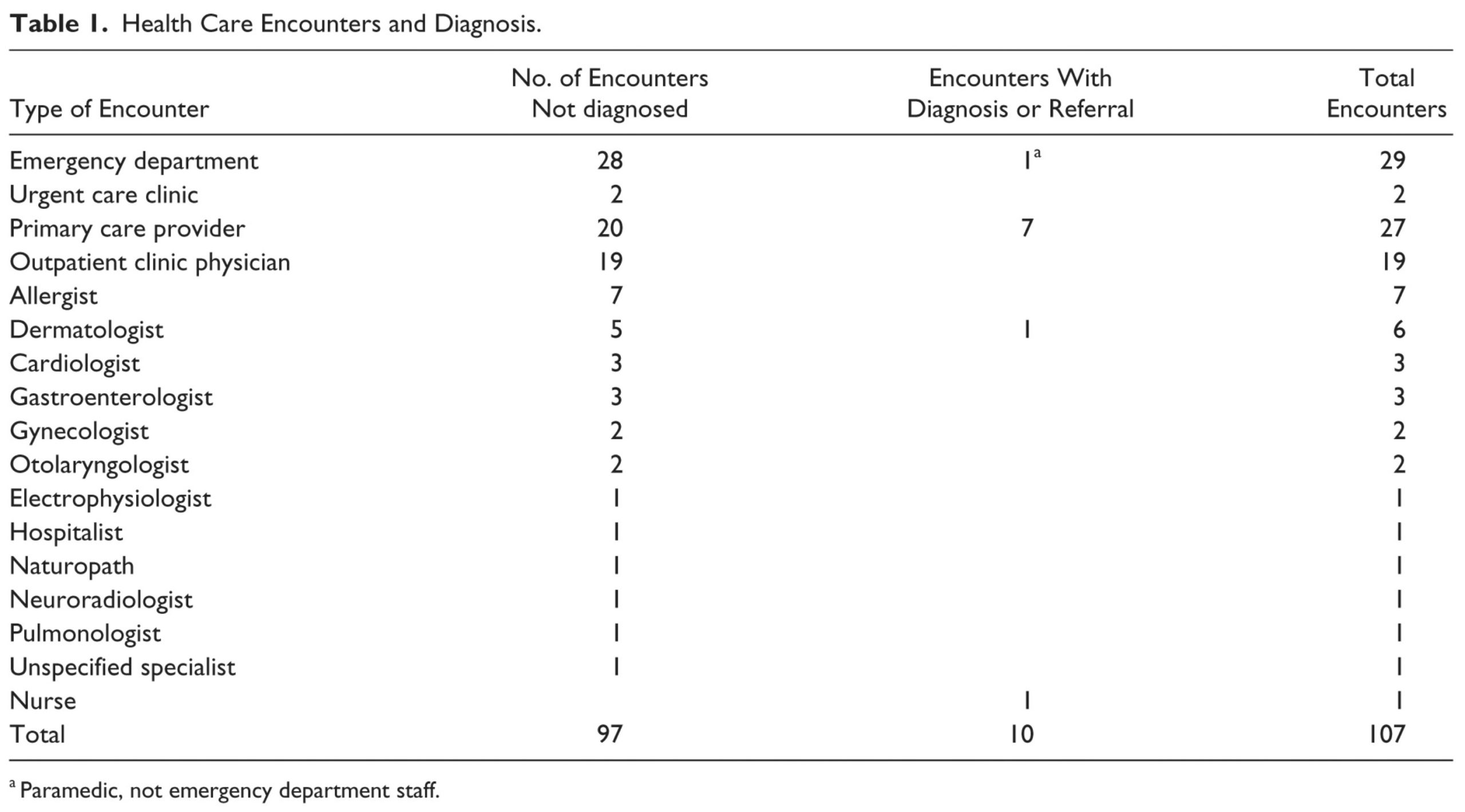

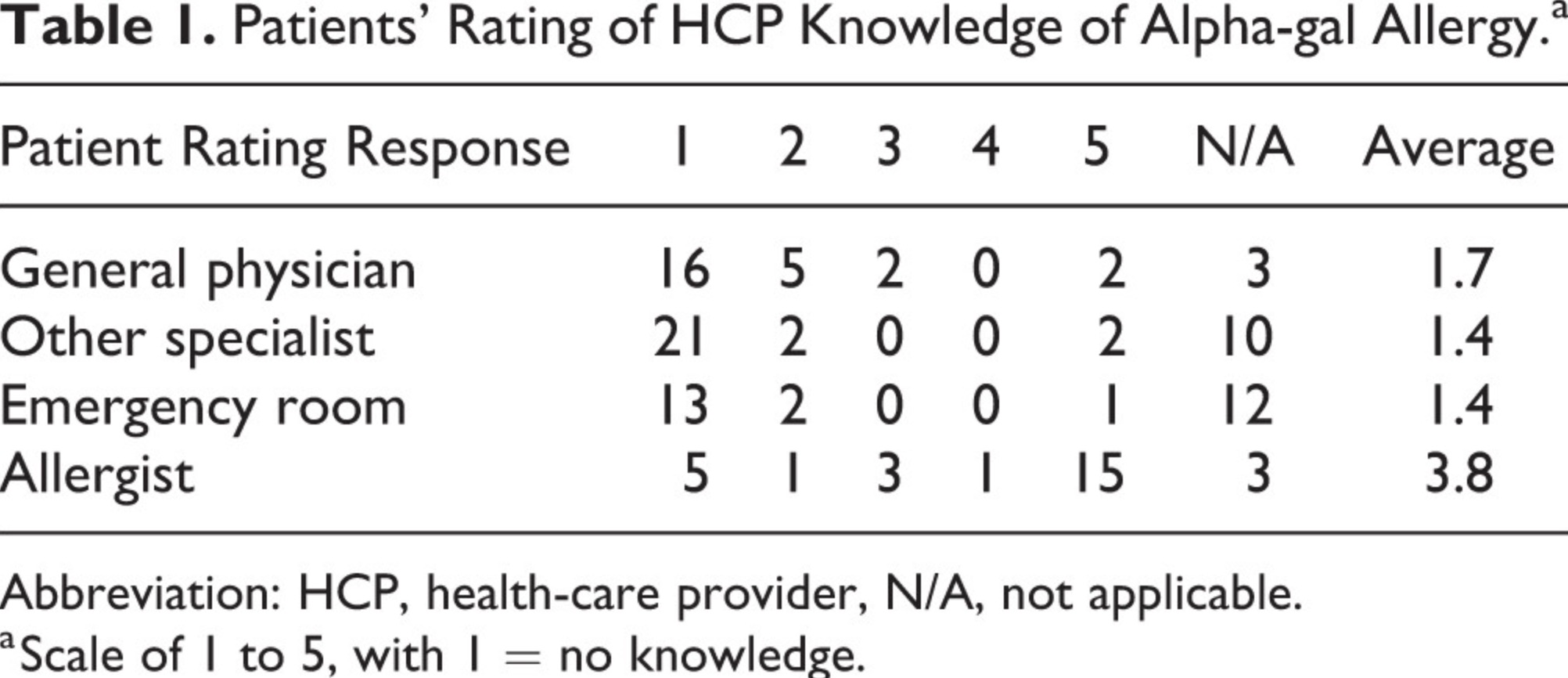

A Lack of Physician Awareness

- Due to its recent discovery, its unusual presentation, and lack of physician awareness, AGS is underdiagnosed and often misdiagnosed (13,14,57).

- Diagnosis tends to be patient-driven, even in areas where AGS is prevalent (14).

- Reports of occurrence are strongly influenced by the efforts of individual research groups and clinicians (15).

- Many people with AGS who only have GI symptoms have had a colonoscopy, endoscopy, and/or cholecystectomy performed before being diagnosed (7).

- In populations with high exposure to known vectors, AGS should be ruled out in cases of unexplained urticaria, angioedema, recurrent anaphylaxis, GI symptoms (7,82,83,84) and even arthritis (60).

Source: Flaherty MG, Kaplan SJ, Jerath MR. Diagnosis of life-threatening alpha-gal food allergy appears to be patient driven. Journal of primary care & community health. 2017 Oct;8(4):345-8.

Source: Flaherty MG, Threats M, Kaplan SJ. Patients’ Health Information Practices and Perceptions of Provider Knowledge in the Case of the Newly Discovered Alpha-gal Food Allergy. Journal of Patient Experience. 2020 Feb;7(1):132-9.

How Do You Get Alpha-gal Syndrome?

- Alpha-gal syndrome is associated with the bite of certain species of ticks. In different parts of the world, different tick species are implicated (15).

- In the United States, the Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum) is thought to be the primary cause of AGS (16), based geographical range and tick salivary factors (57).

- The Asian Longhorned Tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis), recently introduced in the U.S., is known to trigger AGS in Asia (19). As of yet, it has not been tied to any cases in the U.S.

- Alpha-gal has been found in the saliva of Black-Legged Ticks (Ixodes scapularis) (8). It is possible that Black-legged Tick bites may trigger AGS, as do other species in this genus, but this has yet to be demonstrated.

- The Cayenne Tick (Amblyomma cajennense), which is found in southern Texas and Florida (64), has been linked to cases of alpha-gal syndrome in Central America (65).

- Preliminary data suggests that exposure to Ascaris lumbricoides roundworms may play a role in both sensitization to alpha-gal and development of alpha-gal syndrome (106).

- Limited data suggests that bee and wasp stings can cause a rise in alpha-gal IgE, but it has not been shown that they can drive the initial alpha-gal IgE response (57).

- It is likely that additional tick species (8), possibly other ectoparasites (like chiggers (17) and mites (66)) and endoparasites (3,15,18) may be able to sensitize people to alpha-gal. Some may cause levels of sensitization too low to cause clinical reactions (5) and others likely induce full-blown AGS with anaphylactic reactions.

- Only a small percentage of people who are bitten by ticks associated with AGS actually develop clinical symptoms (6).

- Even if you have been bitten by ticks before and did not develop AGS, a future bite could trigger it (3).

- Repeated tick bites are associated with a rise in alpha-gal IgE (20).

- Multiple tick bites are associated with the onset of AGS (3). Many patients report that they were bitten by ticks for many years, and then after being bitten by multiple ticks at once, they developed alpha-gal syndrome.

Ticks and Alpha-gal Syndrome→

Avoiding

Tick Bites→

What to Do If You Are Bitten by a Tick→

Organisms that Glycosylate with Alpha-gal

Primary Sources of Alpha-gal in Food, Drugs, and Other Products

Mammals

Mammals are the primary source of exposure to alpha-gal.

- Alpha-gal is found in the meat, organs, tissues, cells, and fluids of all mammals except for humans, great apes, and Old World monkeys (1).

- Alpha-gal is also found in products made from mammals or that contain ingredients made from them (6,57).

Flounder eggs

The eggs (roe) of some flounder species have been found to contain alpha-gal, and can cause severe reactions in people with AGS (26, 104). See more information below.

Red Algae

Many red algae species make carrageenan, which contains the alpha-gal epitope (54).

What Is a Mammal?→

“Alpha-gal or similar epitopes are ubiquitously expressed on many bacteria, fungi and parasites, as well as in all mammals except for old-world primates and humans ” (122)

Other Organisms That Glycosylate with Alpha-gal

A variety of organisms express alpha-gal, sometimes only in specific tissues. For most of these, there is a lack of evidence as to whether they are associated with reactions in people with alpha-gal syndrome.

- Some fish eggs, in addition to flounder eggs (see above) (58,74,104)

- Green Sea Turtles express high levels of alpha-gal epitopes (108)

- The ocular tissue of some non-mammalian vertebrates (105)

- Cobra venom (58, 110)

- Many invertebrates, including:

- Some human pathogens, such as those that cause malaria, leishmaniasis, and Chagas disease (58).

- Some fungi, including

- Aspergillus mold (107). Whether people with AGS are more likely to have mold allergies is unknown.

- Schizosaccharomyces pombe (112) –yeast used to make millet beer (pombe) in East Africa

- There is no evidence of alpha-gal in mushrooms that we commonly eat, and people with AGS usually tolerate mushrooms.

- Many protozoa (58)

- Many bacteria, including those that live in our gut (58)

- Many viruses, depending on the host they are incubated in (58)

Alpha-gal in Foods

Mammal-Derived Foods

Mammal-derived foods that contain alpha-gal include:

- Mammalian meat

- Mammalian organs

- Other tissue and fluids derived from mammals

- Fat from mammals, like lard

- Broths, boullion, gravy and other foods made from mammals

- Milk and other dairy products

- Gelatin

- Mammalian byproducts

- Some natural flavorings

Other foods and food additives

Flounder eggs (roe)

The eggs (roe) of some flounder have been found to contain alpha-gal or something cross-reactive with it, and can cause severe reactions in people with AGS (26, 104).

Carrageenan

The food additive carrageenan is made from red algae in the order Gigartinales. Like mammals, these algae glycosylate with alpha-gal, and carrageenan also contains the alpha-gal epitope (54).

- Not everyone with AGS reacts to carrageenan, but t least 1-2% of people with AGS report that they do (57).

- Some people with AGS report severe carrageenan reactions with rapid onset.

More Information

Food: First Steps

a guide for people with alpha-gal syndrome→

Cross-contamination

a guide for people with alpha-gal syndrome→

Gelatin

a guide for people with alpha-gal syndrome→

Carrageenan

a guide for people with alpha-gal syndrome→

Mammalian Byproducts

a guide for people with alpha-gal syndrome→

Alpha-gal in Drugs and Medical Products

“Due to the parenteral route of administration, allergists consider alpha-gal-containing drugs even more dangerous for allergic patients than mammalian meat.” (91)

Mammal-Derived Drugs, Medical Products, and Ingredients

Note:

• The risks associated with the use of different medical products that contain mammal-derived ingredients are highly variable and poorly studied.

• There is no data on the risk of reaction associated with many products on this list. They included based on being derived from mammals or containing ingredients derived from mammals. See papers cited for more information.

• Work with your healthcare providers to weigh the relative risks and benefits of using or not using individual medical products that may contain alpha-gal.

Drugs, medical products, and ingredients used in them that may contain mammal-derived materials or ingredients include, but are not limited to, the below.

- Cetuximab (a drug that played a role in the discovery of AGS) (6,30,31,57)

- Cetuximab has caused fatal reactions in people with AGS (86).

- Other monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) produced in non-primate mammalian cell lines (6,57)

- Pancreatic enzyme replacements, such as pancrealipase and other enzyme replacements (e.g. Viokase, Pertzye, Zenpep (Allergan), Creon)(6,36,57,103) and Pancreatin (Now Foods, Bloomingdale, Ill)– an over-the-counter dietary aid (103).

- Thyroid hormone replacements, including Armour Thyroid (Allergan) (57,103)

- EnteraGam (Entera Health, Cary, NC), a bovine immunoglobulin and immunoprotein isolate intended for the management of irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease (103)

- Estrogen therapy drugs that contain estrogen derived from horse urine, e.g. Premarin, Prempro

- Heparin, including low molecular weight heparin such as enoxaparin (Lovenox)(57).

- Dr. Scott Commins reports: “Importantly, we have not had issues with routine heparin prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and our experience suggests this can be safely administered for the over- whelming majority of patients with AGS. There are, undoubtedly, exceptions that will require alternate forms of DVT prophylaxis. Heparin-based reactions that are much more common include those clinical scenarios where heparin is given at high doses for more complete anti-coagulation, such as during heart catheterization, valve procedures, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).” (57).

- There are a number of papers on the use of heparin in patients with AGS, e.g. Safety of Intravenous Heparin for Cardiac Surgery in Patients with Alpha-Gal Syndrome by Hawkins, et al. Search the AGI Publications Database using keyword “heparin” for more information.

- Perioperative implications of patients with alpha-gal allergies by Nourian, et al includes a risk stratification algorithm for AGS patients requiring perioperative parenteral anticoagulation.

- NOTE: Fondaparinux, which is NOT animal-derived can sometimes used in place of heparin for some purposes (121).

- Heparin treated products, such as heparin-coated vascular grafts e.g. GORE® PROPATEN® Vascular Graft

- Gelatin-based plasma volume expanders, such as Gelafundin, Gelofusine, Gelaspan, Haemaccel (not commonly used in the U.S. if at all) (6,28,52,57,101).

- Many vaccines, including those that contain gelatin or other mammalian byproducts. Gelatin appears to be the most problematic vaccine ingredient for people with AGS.

- Antivenom, such as crotalidae polyvalent immune Fab (CroFab) (6,50,51,57)

- Bioprosthetic (bovine and porcine) heart valves (6,45,46,47,48,49,57,103) including:

- Other products made from mammalian tissue or organs, such as:

- Heart/pericardial/epicardial patches, e.g. CorMatrix Cor™ PATCH (103) and XenoSure Biologic Patch

- Photofix (decellularized bovine pericardium (Cryolife, Kennesaw, Ga)– used in heart and vascular repair (103)

- Collagen scaffolding, e.g. Cardiocel acellular collagen scaffold (LeMaitre Vascular, Burlington, Mass)– used in heart and vascular repair (103)

- Extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffolds

- Hernia mesh (121) e.g. OviTex

- Orthopedic implants (121)

- Mammal-derived and collagen-impregnated vascular grafts (124) e.g. ProCol bovine mesenteric vein (LeMaitre Vascular) (103), Artegraft Collagen Vascular Graft, Hemashield

- And more

- Hemostatic agents, such as:

- Surgiflo (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH) (53)

- FloSeal hemostatic matrix (Baxter International, Deerfield, IL) (6, 121)

- Surgifoam powder (Ethicon, Raritan, NJ, USA)(6, 121)

- Absorbable gelatin sponge (6,121), like Gelfoam (Pfizer, New York, NY)

- Thrombin sprays which are porcine- and hamster-derived, like Recothrom (Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA)(121)

- Embolics, such as:

- Obsidio Embolic (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) (123)

- Products that contain hemostatic agents, including vascular closure devices VCDs (123) such as:

- Angio-Seal VIP Vascular Closure Device (Terumo Medical, Somerset, NJ) (123)

- Vascade MVP Venous Vascular Closure System (Haemonetics, Boston, MA) (123)

- Vascade Vascular Closure System (Haemonetics, Boston, MA) (123)

- Manta Vascular Closure Device (Teleflex, Morrisville, NC) (123)

- Manual compression or alternative VCDs which do not contain mammal-derived products, such as suture-based closure devices, may be considered as alternatives. (123)

- Other products that contain gelatin/collagen, such as:

- Many other perioperative, prescription, and OTC drugs (32,33,34,35,57). Some of these pose a known risk to people with AGS; others contain mammalian byproducts for which there is little data on alpha-gal content or their ability to contribute to clinical reactions, such as:

- Stearic acid

- Magnesium stearate (38) (in many tablets)

- Glycerin (in many suspensions)

- Lactose and lactose derivatives

- Dairy byproducts in drugs and vaccines including (but are not limited to), casamino acids, casein, and lactalbumin.

- Lactose alone is used in more than 20% of prescription drugs and about 6% in over-the-counter medicines.

- Many other medical products and devices, may contain mammal-derived products, including (but not limited to):

- Collagen/catgut and sutures, e.g. chromic sutures, plain gut sutures, mild chromic gut sutures

- We are not aware of any literature on reactions to collagen sutures, but a number of anecdotes, including reports of adverse outcomes, such as infection and disfigurement, have been shared in AGS support groups.

- For more information on which sutures are and are not derived from mammals, see this article from the VeganMed pharmacists.

- Lubricants (e.g. gelatin-based)

- Topicals (e.g. contain gelatin and lanolin)

- Adhesives (including bandage adhesives)

- Collagen/thrombin glues (121)

- Propofol (e.g. if glycerin used to rehydrate it is mammal-derived) (121)

- Intralipid (e.g. if glycerin mammal-derived) (121)

- See 6,32, 33, 34, 35, 102, 121 for more information.

- Collagen/catgut and sutures, e.g. chromic sutures, plain gut sutures, mild chromic gut sutures

- Some products used in dentistry.

See also below information about carrageenan

Carrageenan in Drugs and Medical Products

Medications other medical products that can contain carrageenan

Carrageenan is made from red algae, not mammals, but contains the alpha-gal epitope (54).

- At least 1-2% of people with AGS react to carrageenan (57) in foods.

- There is no published information about the relevance of carrageenan in medical products for people with AGS and very little even in the way of anecdotal information.

- Carrageenan in drugs and medical products may or may not be medically relevant for people with alpha-gal syndrome; more research is needed.

Based on limited information about carrageenan in medications and medical products, it appears to be used in the below products. There may be many other medical products that contain carrageenan; we have not been able to find much information about this.

- Numerous medications, both as an active ingredient (for example, in cough remedies, laxatives and medications for other intestinal issues) and as an inactive ingredient, including as a thickening agent in liquid medications, a coating agent, and as a polymer matrix in time-release medications.

- Bone graft substitutes, entrapping vessels such as biobeads and encapsulation vehicles for drug delivery, hydrogels, and nasal sprays.

- Other medical products (76), including some barium enemas (55).

- An unknown number of other medications and medical products.

Other Alpha-gal Exposures

Airborne Alpha-gal

Airborne exposures

Some people with AGS report reactions to airborne forms of alpha-gal (57), including:

- Suspended fat droplets in smoke or fumes from cooking meat, especially from grills

- Other forms of airborne alpha-gal

Support for people with reactions to airborne alpha-gal

There is a Facebook support groups for people who react to airborne alpha-gal.

Reactions to Airborne Alpha-gal

a guide for people with alpha-gal syndrome→

Mammal-derived Ingredients in Personal Care and Household Products

Personal care and household products that can have mammal-derived ingredients

Products containing “hydrolyzed protein” (gelatin), lanolin, glycerin, collagen, and tallow tend to be the most problematic. Hundreds of additional mammalian ingredients whose alpha-gal content is unknown are also added to personal care and household products, including:

- Skin care products, including lotion

- Hair products, such as shampoo and conditioner

- Make-up

- Deodorants and antiperspirants

- Liquid soaps and other cleansers

- Toothpaste

- Hand sanitizers

- Latex condoms

- Personal lubricants

- Perfumes

- Toilet paper, which is sometimes impregnated with gelatin

- Many cleaning products

- Dryer sheets made with lanolin– these are problematic for many of us, triggering both airborne reactions and rashes.

- Detergents and fabric softeners, such as Downy fabric softener

- Crayons

Personal Care Products

a guide for people with alpha-gal syndrome→

Carrageenan in Personal Care and Household Products

Carrageenan

Carrageenan is made from red algae, not mammals, but contains the alpha-gal epitope (54).

- At least 1-2% of people with AGS react to carrageenan (57).

- Some people with AGS react to carrageenan in personal care and household products, as well as in food.

Personal care and household products that can contain carrageenan

- Many toothpastes

- Liquid soaps and other cleansers

- Skin care products

- Hair products

- Make-up

- Air fresheners

- See the Environmental Working Group’s Skin Deep database for more information about personal care products that contain carrageenan.

What Foods CAN We Eat?

As far as we know, alpha-gal is not typically found in:

- Birds, like chicken, turkey, quail, and emu don’t normally express alpha-gal (58).

- Most reptiles, like snakes, crocodiles, and lizards (58), although Green Sea Turtles have high levels of alpha-gal epitopes (108) and cobra venom also contains it (58)

- Alligator meat does not seem to be a problem for most people with AGS

- Amphibians, like frogs, with the exception of some amphibian eggs (58)

- Fish or seafood (58) except for flounder eggs (26, 104) and the eggs of some other teleost (bony) fish (58,74,104)

- Crustaceans, like shrimp, prawns, crawfish, crabs, and lobster

- Molluscs, like oysters, mussels, and clams

- Plants, including fruits, vegetables, and grains

- Note that algae are not plants, and red algae (seaweed) do contain alpha-gal.

- Edible fungi, like mushrooms

- Possible exception: koji, which is made from aspergillus fungi

Watch out for:

- Poultry sausages may have casings made from the intestines of mammals.

- Some of these foods–especially chicken, turkey, and seafood–may be injected, treated or sprayed with mammalian substances or carrageenan or otherwise contaminated by them. These may be listed among the ingredients, but if they are considered a processing aid, as with gelatin used to clarify juice and wine or carrageenan sprayed on cut fruit or fish, they will not be.

- Some people with AGS report reacting to canned tuna (6) for reasons that are not clear but which may be related to the use of processing agents or fillers.

- There are unverified, anecdotal reports of people who are highly sensitive to alpha-gal reacting to chicken eggs when the chicken are not fed a vegetarian diet. Duck eggs or eggs from chickens fed a vegetarian diet may be better tolerated in these rare cases.

In general, the less processed your food, the less likely it is to contain alpha-gal. Read labels and buy from trusted sources. Be careful when eating out. Cooking your own food will help you avoid alpha-gal.

More Information

Checklist for the Newly Diagnosed→

Determining Your Tolerance: First Steps

a guide for people with alpha-gal syndrome→

Help Find a Cure→

Physician Experts→

Publications Database→

References

1. Commins SP, Satinover SM, Hosen J, Mozena J, Borish L, Lewis BD, Woodfolk JA, Platts-Mills TA. Delayed anaphylaxis, angioedema, or urticaria after consumption of red meat in patients with IgE antibodies specific for galactose-α-1, 3-galactose. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2009 Feb 1;123(2):426-33.

2. Commins S, Lucas S, Hosen J, Satinover SM, Borish L, Platts-Mills TA. Anaphylaxis and IgE antibodies to galactose-alpha-1, 3-galactose (alphaGal): insight from the identification of novel IgE ab to carbohydrates on mammalian proteins. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2008 Feb 1;121(2):S25.

3. Commins SP, James HR, Kelly LA, Pochan SL, Workman LJ, Perzanowski MS, Kocan KM, Fahy JV, Nganga LW, Ronmark E, Cooper PJ. The relevance of tick bites to the production of IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-α-1, 3-galactose. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011 May 1;127(5):1286-93.

4. Soh JY, Huang CH, Lee BW. Carbohydrates as food allergens. Asia Pacific Allergy. 2015 Jan 1;5(1):17-24.

5. Levin M, Apostolovic D, Biedermann T, Commins SP, Iweala OI, Platts-Mills TA, Savi E, van Hage M, Wilson JM. Galactose α-1, 3-galactose phenotypes: Lessons from various patient populations. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2019 Jun 1;122(6):598-602.

6. Platts-Mills TA, Li RC, Keshavarz B, Smith AR, Wilson JM. Diagnosis and management of patients with the α-Gal syndrome. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2020 Jan 1;8(1):15-23.

7. Commins SP. Invited commentary: alpha-gal allergy: tip of the iceberg to a pivotal immune response. Current allergy and asthma reports. 2016 Sep 1;16(9):61.

8. Crispell G, Commins SP, Archer-Hartman SA, Choudhary S, Dharmarajan G, Azadi P, Karim S. Discovery of alpha-gal-containing antigens in North American tick species believed to induce red meat allergy. Frontiers in immunology. 2019 May 17;10:1056.

9. Monzón JD, Atkinson EG, Henn BM, Benach JL. Population and evolutionary genomics of Amblyomma americanum, an expanding arthropod disease vector. Genome biology and evolution. 2016 May 1;8(5):1351-60.

10. Raghavan RK, Peterson AT, Cobos ME, Ganta R, Foley D. Current and future distribution of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum (L.)(Acari: Ixodidae) in North America. PLoS One. 2019 Jan 2;14(1):e0209082.

11. Wilson JM, Platts-Mills TA. Red meat allergy in children and adults. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. 2019 Jun 1;19(3):229-35.

12. Commins, SP. (2018). Retrieved from: More people developing red meat allergy from tick bites. CBS News

13. Flaherty MG, Threats M, Kaplan SJ. Patients’ Health Information Practices and Perceptions of Provider Knowledge in the Case of the Newly Discovered Alpha-gal Food Allergy. Journal of Patient Experience. 2020 Feb;7(1):132-9.

14. Flaherty MG, Kaplan SJ, Jerath MR. Diagnosis of life-threatening alpha-gal food allergy appears to be patient driven. Journal of primary care & community health. 2017 Oct;8(4):345-8.

15. Cabezas-Cruz A, Hodžić A, Román-Carrasco P, Mateos-Hernández L, Duscher GG, Sinha DK, Hemmer W, Swoboda I, Estrada-Peña A, De La Fuente J. Environmental and molecular drivers of the α-Gal syndrome. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019 May 31;10:1210.

16. Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA. Tick bites and red meat allergy. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. 2013 Aug;13(4):354.

17. Stoltz LP, Cristiano LM, Dowling AP, Wilson JM, Platts-Mills TA, Traister RS. Could chiggers be contributing to the prevalence of galactose-alpha-1, 3-galactose sensitization and mammalian meat allergy?. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice. 2019 Feb;7(2):664.

18. Arkestål K, Sibanda E, Thors C, Troye-Blomberg M, Mduluza T, Valenta R, Grönlund H, van Hage M. Impaired allergy diagnostics among parasite-infected patients caused by IgE antibodies to the carbohydrate epitope galactose-α1, 3-galactose. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011 Apr 1;127(4):1024-8.

19. Chinuki Y, Ishiwata K, Yamaji K, Takahashi H, Morita E. Haemaphysalis longicornis tick bites are a possible cause of red meat allergy in Japan. Allergy. 2016 Mar;71(3):421-5.

20. Hashizume H, Fujiyama T, Umayahara T, Kageyama R, Walls AF, Satoh T. Repeated Amblyomma testudinarium tick bites are associated with increased galactose-α-1, 3-galactose carbohydrate IgE antibody levels: a retrospective cohort study in a single institution. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018 Jun 1;78(6):1135-41.

21. Bianchi, John (2019). Personal communication

22. Morisset M, Richard C, Astier C, Jacquenet S, Croizier A, Beaudouin E, Cordebar V, Morel‐Codreanu F, Petit N, Moneret‐Vautrin DA, Kanny G. Anaphylaxis to pork kidney is related to IgE antibodies specific for galactose‐alpha‐1, 3‐galactose. Allergy. 2012 May;67(5):699-704.

23. Fischer J, Hebsaker J, Caponetto P, Platts-Mills TA, Biedermann T. Galactose-alpha-1, 3-galactose sensitization is a prerequisite for pork-kidney allergy and cofactor-related mammalian meat anaphylaxis. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2014 Sep 1;134(3):755-9.

24. Fischer J, Yazdi AS, Biedermann T. Clinical spectrum of α-Gal syndrome: from immediate-type to delayed immediate-type reactions to mammalian innards and meat. Allergo journal international. 2016 Mar 1;25(2):55-62.

25. McPherson TB, Liang H, Record RD, Badylak SF. Galα (1, 3) Gal epitope in porcine small intestinal submucosa. Tissue engineering. 2000 Jun 1;6(3):233-9.

26. Fujiwara M, Araki T. Immediate anaphylaxis due to beef intestine following tick bites. Allergology International. 2019;68(1):127-9.

27. Caponetto P, Fischer J, Biedermann T. Gelatin-containing sweets can elicit anaphylaxis in a patient with sensitization to galactose-α-1, 3-galactose. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2013 May 1;1(3):302-3.

28. Mullins RJ, James H, Platts-Mills TA, Commins S. Relationship between red meat allergy and sensitization to gelatin and galactose-α-1, 3-galactose. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2012 May 1;129(5):1334-42.

29. Kaman K, Robertson D. ALPHA-GAL ALLERGY; MORE THAN MEAT?. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2018 Nov 1;121(5):S115.

30. Chung CH, Mirakhur B, Chan E, Le QT, Berlin J, Morse M, Murphy BA, Satinover SM, Hosen J, Mauro D, Slebos RJ. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-α-1, 3-galactose. New England journal of medicine. 2008 Mar 13;358(11):1109-17.

31. Berg EA, Platts-Mills TA, Commins SP. Drug allergens and food—the cetuximab and galactose-α-1, 3-galactose story. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2014 Feb 1;112(2):97-101.

32. Dunkman WJ, Rycek W, Manning MW. What does a red meat allergy have to do with anesthesia? Perioperative management of alpha-gal syndrome. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2019 Nov 1;129(5):1242-8.

33. Pfützner W, Brockow K. Perioperative drug reactions–practical recommendations for allergy testing and patient management. Allergo journal international. 2018 Jun 1;27(4):126-9.

34. Dewachter P, Kopac P, Laguna JJ, Mertes PM, Sabato V, Volcheck GW, Cooke PJ. Anaesthetic management of patients with pre-existing allergic conditions: a narrative review. British journal of anaesthesia. 2019 Jul 1;123(1):e65-81.

35. Popescu FD, Cristea OM, IONICĂ FE, Vieru M. DRUG ALLERGIES DUE TO IgE SENSITIZATION TO α-GAL. magnesium. 2018;2017:47-8.

36. Swiontek K, Morisset M, Codreanu-Morel F, Fischer J, Mehlich J, Darsow U, Petitpain N, Biedermann T, Ollert M, Eberlein B, Hilger C. Drugs of porcine origin—A risk for patients with α-gal syndrome?. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2019 May 1;7(5):1687-90.

37. Vidal C, Mendez-Brea P, Lopez-Freire S, Gonzalez-Vidal T. Vaginal Capsules: An Unsuspected Probable Source of Exposure to α-Gal. Journal of investigational allergology & clinical immunology. 2016;26(6):388.

38. Muglia C, Kar I, Gong M, Hermes-DeSantis ER, Monteleone C. Anaphylaxis to medications containing meat byproducts in an alpha-gal sensitized individual. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice. 2015;3(5):796.

39. Akella K, Patel H, Wai J, Roppelt H, Capone D. Alpha Gal-Induced Anaphylaxis to Herpes Zoster Vaccination. Chest. 2017 Oct 1;152(4):A6.

40. Bakhtiar MF, Leong KW, Kwok FY, Hui MT, Tang MM, Joseph CT, Bathumana‐Appan PP, Nagum AR, ZHM Y, Murad S. P66: ALLERGIC REACTION TO BOVINE GELATIN COLLOID: THE ROLE OF IMMUNOGLOBULIN E TOWARDS GALACTOSE‐ALPHA‐1, 3‐GALACTOSE: IMPLICATIONS BEYOND RED MEAT ALLERGIES. Internal Medicine Journal. 2017 Sep;47:24-.

41. Bradfisch F, Pietsch M, Forchhammer S, Strobl S, Stege HM, Pietsch R, Carstens S, Schäkel K, Yazdi A, Saloga J. Case series of anaphylactic reactions after rabies vaccinations with gelatin sensitization. Allergo Journal International. 2019 Jun 1;28(4):103-6.

42. Stone CA, Commins SP, Choudhary S, Vethody C, Heavrin JL, Wingerter J, Hemler JA, Babe K, Phillips EJ, Norton AE. Anaphylaxis after vaccination in a pediatric patient: further implicating alpha-gal allergy. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2019 Jan 1;7(1):322-4.

43. Stone CA, Hemler JA, Commins SP, Schuyler AJ, Phillips EJ, Peebles RS, Fahrenholz JM. Anaphylaxis after zoster vaccine: Implicating alpha-gal allergy as a possible mechanism. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2017 May 1;139(5):1710-3.

44. Pattanaik D, Lieberman P, Lieberman J, Pongdee T, Keene AT. The changing face of anaphylaxis in adults and adolescents. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2018 Nov 1;121(5):594-7.

45. Ankersmit HJ, Copic D, Simader E. When meat allergy meets cardiac surgery: A driver for humanized bioprosthesis. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2017 Oct 1;154(4):1326-7.

46. Hawkins RB, Frischtak HL, Kron IL, Ghanta RK. Premature bioprosthetic aortic valve degeneration associated with allergy to galactose‐alpha‐1, 3‐galactose. Journal of cardiac surgery. 2016 Jul;31(7):446-8.

47. Kleiman AM, Littlewood KE, Groves DS. Delayed anaphylaxis to mammalian meat following tick exposure and its impact on anesthetic management for cardiac surgery: a case report. A&A Practice. 2017 Apr 1;8(7):175-7.

48. Mozzicato SM, Tripathi A, Posthumus JB, Platts-Mills TA, Commins SP. Porcine or bovine valve replacement in three patients with IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1, 3-galactose. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice. 2014 Sep;2(5):637.

49. Mangold A, Szerafin T, Hoetzenecker K, Hacker S, Lichtenauer M, Niederpold T, Nickl S, Dworschak M, Blumer R, Auer J, Ankersmit HJ. Alpha-Gal specific IgG immune response after implantation of bioprostheses. The Thoracic and cardiovascular surgeon. 2009 Jun;57(04):191-5.

50. Fischer J, Eberlein B, Hilger C, Eyer F, Eyerich S, Ollert M, Biedermann T. Alpha‐gal is a possible target of IgE‐mediated reactivity to antivenom. Allergy. 2017 May;72(5):764-71.

51. Rizer J, Brill K, Charlton N, King J. Acute hypersensitivity reaction to Crotalidae polyvalent immune Fab (CroFab) as initial presentation of galactose-α-1, 3-galactose (α-gal) allergy. Clinical Toxicology. 2017 Aug 9;55(7):668-9.

52. Farooque S, Kenny M, Marshall SD. Anaphylaxis to intravenous gelatin‐based solutions: a case series examining clinical features and severity. Anaesthesia. 2019 Feb;74(2):174-9.

53. Lied GA, Lund KB, Storaas T. Intraoperative anaphylaxis to gelatin-based hemostatic agents: a case report. Journal of asthma and allergy. 2019;12:163.

54. Tobacman JK. The common food additive carrageenan and the alpha-gal epitope. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2015 Dec 1;136(6):1708-9.

55. Tarlo SM, Dolovich J, Listgarten C. Anaphylaxis to carrageenan: A pseudo–latex allergy. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1995 May 1;95(5):933-6.

56. Steinke JW, Platts-Mills TAE, Schuyler A, Commins SP. Reply to “The common food additive carrageenan and the alpha-gal epitope”. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2015 Oct 28;136(6):1709-10

57. Commins SP. Diagnosis & management of alpha-gal syndrome: lessons from 2,500 patients. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 2020 Jul 9:1-1.

58. Galili, U., & Avila, J. L. (Eds.). (2012). α–Gal and Anti–Gal: α1, 3–Galactosyltransferase, α–Gal Epitopes, and the Natural Anti–Gal Antibody Subcellular Biochemistry (Vol. 32). Springer Science & Business Media.

59. Fischer J, Lupberger E, Hebsaker J, Blumenstock G, Aichinger E, Yazdi AS, Reick D, Oehme R, Biedermann T. Prevalence of type I sensitization to alpha‐gal in forest service employees and hunters. Allergy. 2017 Oct;72(10):1540-7.

60. SAT0456 SERO-REACTIVITY TO GALACTOSE-ALPHA-1,3-GALACTOSE AND CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS OF PATIENTS SEEN IN A RHEUMATOLOGY OUTPATIENT PRACTICE. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2019 Jun 15;78:1317-8.

61. Bianchi J, Walters A, Fitch ZW, Turek JW. Alpha-gal syndrome: Implications for cardiovascular disease. Global Cardiology Science and Practice. 2020 Feb 9;2019(3).

62. Carter MC, Ruiz‐Esteves KN, Workman L, Lieberman P, Platts‐Mills TA, Metcalfe DD. Identification of alpha‐gal sensitivity in patients with a diagnosis of idiopathic anaphylaxis. Allergy. 2018 May;73(5):1131-4.

63. Binder AM, Commins SP, Altrich ML, et al. Diagnostic testing for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose, United States, 2010 to 2018. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(4):411-416.e1.

64. I-TICK Surveillance. Retrieved from: https://twitter.com/ITickUIUC/status/1282799807996854278

65. Wickner PG, Commins SP. The first 4 Central American cases of delayed meat allergy with galactose-alpha-1, 3-galactose positivity clustered among field biologists in Panama. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014 Feb 1;133(2):AB212.

66. Ohshita N, Ichimaru Y, Gamoh S, Tsuji K, Kishimoto N, Tsutsumi YM, Momota Y. Management of infusion reactions associated with cetuximab treatment: A case report. Molecular and Clinical Oncology. 2017 Jun 1;6(6):853-5.

67. Stein D, Schuyler A, Commins S, Behm B, Chitnavis M. P-002 YI First Dose IgE-Mediated Allergy to Infliximab Due to Galactose-α-1, 3-Galactose Allergy. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2016 Mar 1;22:S9-10.

68. Van Tine BA, Govindarajan R, Attia S, Somaiah N, Barker SS, Shahir A, Barrett E, Lee P, Wacheck V, Ramage SC, Tap WD. Incidence and management of olaratumab infusion-related reactions. Journal of oncology practice. 2019 Nov;15(11):e925-33.

69. Venturini M, Lobera T, Sebastián A, Portillo A, Oteo JA. IgE to α-Gal in Foresters and Forest Workers From La Rioja, North of Spain. Journal of investigational allergology & clinical immunology. 2018;28(2):106.

70. Apostolovic D, Tran TA, Hamsten C, Starkhammar M, Cirkovic Velickovic T, van Hage M. Immunoproteomics of processed beef proteins reveal novel galactose‐α‐1, 3‐galactose‐containing allergens. Allergy. 2014 Oct;69(10):1308-15.

71. Khora SS, Navya P. Bioactive Polysaccharides from Marine Macroalgae. Encyclopedia of Marine Biotechnology. 2020 Aug 4.

72. Gowda DC, Glushka J, Halbeek HV, Thotakura RN, Bredehorst R, Vogel CW. N-linked oligosaccharides of cobra venom factor contain novel α (1-3) galactosylated Lex structures. Glycobiology. 2001 Mar 1;11(3):195-208.

73. Hodžić A, Mateos-Hernández L, Fréalle E, Román-Carrasco P, Alberdi P, Pichavant M, Risco-Castillo V, Le Roux D, Vicogne J, Hemmer W, Auer H. Infection with Toxocara canis Inhibits the Production of IgE Antibodies to α-Gal in Humans: Towards a Conceptual Framework of the Hygiene Hypothesis?. Vaccines. 2020 Jun;8(2):167.

74. Taguchi T, Kitajima K, Muto Y, Inoue S, Khoo KH, Morris HR, Dell A, Wallace RA, Selman K, Inoue Y. A precise structural analysis of a fertilization-associated carbohydrate-rich glycopeptide isolated from the fertilized eggs of euryhaline killi fish (Fundulus heteroclitus). Novel penta-antennary N-glycan chains with a bisecting N-acetylglucosaminyl residue. Glycobiology. 1995 Sep 1;5(6):611-24.

75. Shao Y, Yu Y, Pei CG, Qu Y, Gao GP, Yang JL, Zhou Q, Yang L, Liu QP. The expression and distribution of α-Gal gene in various species ocular surface tissue. International journal of ophthalmology. 2012;5(5):543.

76. Chauhan PS, Saxena A. Bacterial carrageenases: an overview of production and biotechnological applications. 3 Biotech. 2016 Dec 1;6(2):146.

77. USDA Carrageenan Handling/Processing

78. van Nunen S. Galactose-alpha-1, 3-galactose, mammalian meat and anaphylaxis: a world-wide phenomenon?. Current Treatment Options in Allergy. 2014 Sep 1;1(3):262-77.

79. Wilson JM, Nguyen AT, Schuyler AJ, Commins SP, Taylor AM, Platts-Mills TA, McNamara CA. IgE to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-α-1, 3-galactose is associated with increased atheroma volume and plaques with unstable characteristics—brief report. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2018 Jul;38(7):1665-9.

80. Wilson JM, McNamara CA, Platts-Mills TA. IgE, α-Gal and atherosclerosis. Aging (Albany NY). 2019 Apr 15;11(7):1900.

81. Tina Merritt, MD, personal communication.

82. Hodgeman N, Horn CL, Paredes A. An Unusual Mimicker of Irritable Bowel Disease: 1855. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2019 Oct 1;114(2019 ACG Annual Meeting Abstracts):S1039.

83. Bensinger A, Green P. Mammalian Meat Allergy Masquerading as IBS-D: 1846. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2019 Oct 1;114(2019 ACG Annual Meeting Abstracts):S1036-7.

84. Mabelane T, Basera W, Botha M, Thomas HF, Ramjith J, Levin ME. Predictive values of alpha‐gal IgE levels and alpha‐gal IgE: Total IgE ratio and oral food challenge‐proven meat allergy in a population with a high prevalence of reported red meat allergy. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2018 Dec;29(8):841-9.

85. Armstrong P, Binder A, Amelio C, Kersh G, Biggerstaff B, Beard C, Petersen L, Commins S. Descriptive Epidemiology of Patients Diagnosed with Alpha-gal Allergy—2010–2019. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2020 Feb 1;145(2):AB145.

86. Pointreau Y, Commins SP, Calais G, Watier H, Platts-Mills TA. Fatal infusion reactions to cetuximab: role of immunoglobulin E–mediated anaphylaxis. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012 Jan 20;30(3):334.

87. van Nunen S. Tick-induced allergies: mammalian meat allergy, tick anaphylaxis and their significance. Asia Pacific Allergy. 2015 Jan 1;5(1):3-16.

88. van Nunen S, O’Connor K, Fernando S, Clarke L, Boyle R. THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN IXODES HOLOCYCLUS TICK BITE REACTIONS AND RED MEAT ALLERGY: P17. Internal Medicine Journal. 2007 Nov 1;37.

89. Van Nunen SA, O’Connor KS, Clarke LR, Boyle RX, Fernando SL. An association between tick bite reactions and red meat allergy in humans. The Medical journal of Australia. 2009 May 4;190(9):510-1.

90. Meat Allergy Tirggered by a Tick Bite with Eri McGintee retrieved from: https://youtu.be/hj96Vvr1WhQ

91. Fischer J, Huynh HN, Hebsaker J, Forchhammer S, Yazdi AS. Prevalence and Impact of Type I Sensitization to Alpha-Gal in Patients Consulting an Allergy Unit. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2020;181(2):119-27.

92. Platts-Mills TA, Commins SP, Biedermann T, van Hage M, Levin M, Beck LA, Diuk-Wasser M, Jappe U, Apostolovic D, Minnicozzi M, Plaut M. On the cause and consequences of IgE to galactose-α-1, 3-galactose: a Report from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Workshop on Understanding IgE-Mediated Mammalian Meat Allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2020 Feb 10.

93. Takahashi H, Chinuki Y, Tanaka A, Morita E. Laminin γ‐1 and collagen α‐1 (VI) chain are galactose‐α‐1, 3‐galactose–bound allergens in beef. Allergy. 2014 Feb;69(2):199-207.

94. Hilger C, Fischer J, Swiontek K, Hentges F, Lehners C, Eberlein B, Morisset M, Biedermann T, Ollert M. Two galactose‐α‐1, 3‐galactose carrying peptidases from pork kidney mediate anaphylactogenic responses in delayed meat allergy. Allergy. 2016 May;71(5):711-9.

95. Iweala OI, Choudhary SK, Addison CT, Batty CJ, Kapita CM, Amelio C, Schuyler AJ, Deng S, Bachelder EM, Ainslie KM, Savage PB. Glycolipid-mediated basophil activation in alpha-gal allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2020 Feb 20.

96. Iweala O, Brennan PJ, Commins SP. Serum IgE specific for alpha-Gal sugar moiety can bind glycolipid. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2017 Feb 1;139(2):AB88.

97. Iweala OI, Choudhary SK, Addison CT, Batty CJ, Kapita CM, Amelio C, Schuyler AJ, Deng S, Bachelder EM, Ainslie KM, Savage PB. Glycolipid-mediated basophil activation in alpha-gal allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2020 Feb 20.

98. Villalta D, Pantarotto L, Da Re M, Conte M, Sjolander S, Borres MP, Martelli P. High prevalence of sIgE to Galactose‐α‐1, 3‐galactose in rural pre‐Alps area: a cross‐sectional study. Clinical & Experimental Allergy. 2016 Feb;46(2):377-80.

99. Galili U, Clark MR, Shohet SB, Buehler J, Macher BA. Evolutionary relationship between the natural anti-Gal antibody and the Gal alpha 1—-3Gal epitope in primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1987 Mar 1;84(5):1369-73.

100. Wilson JM, Platts-Mills TA. The oligosaccharide galactose-α-1, 3-galactose and the α-Gal syndrome: insights from an epitope that is causal in immunoglobulin E-mediated immediate and delayed anaphylaxis. Eur Med J. 2018;3:89-98.

101. Zurbano-Azqueta L, Antón-Casas E, Duque-Gómez S, Jiménez-Gómez I, Fernández-Pellón L, López-Gutiérrez J. Alpha-gal syndrome. Allergy to red meat and gelatin. Revista Clínica Española (English Edition). 2021 Oct 14.

102. Christian RA, Stabile KJ, Gupta AK, Leckey Jr BD, Cardona DM, Nowinski RJ, Kelly JD, Toth AP. Histologic Analysis of Porcine Dermal Graft Augmentation in Treatment of Rotator Cuff Tears. The American journal of sports medicine. 2021 Oct 15:03635465211049434.

103. Kuravi KV, Sorrells LT, Nellis JR, et al. Allergic response to medical products in patients with alpha-gal syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. Published online April 9, 2021. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.03.100

104. Chinuki Y, Morita E, Takahashi H. IgE antibodies to galactose-a-1,3-galactose, an epitope of red meat allergen, cross-react with a novel flounder roe allergen. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. Published online October 15, 2021:0.

105. Shao Y, Yu Y, Pei C-G, et al. The expression and distribution of α-Gal gene in various species ocular surface tissue. Int J Ophthalmol. 2012;5(5):543.

106. Murangi T, Prakash P, Moreira BP, et al. Ascaris lumbricoides and ticks associated with sensitisation to Galactose α1,3-galactose and elicitation of the alpha-gal syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Published online July 29, 2021. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2021.07.018

107. Mateos-Hernández L, Risco-Castillo V, Torres-Maravilla E, et al. Gut Microbiota Abrogates Anti-α-Gal IgA Response in Lungs and Protects against Experimental Aspergillus Infection in Poultry. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(2). doi:10.3390/vaccines8020285

108. Aspergillus oryzae, Wikipedia

109. Murugan AVM, Oliveira T, Alagesan K, et al. Evolutionary Glycomics: A Comprehensive Study of Vertebrate Host Serum/Plasma Glycome Using Orthogonal Glycomics Techniques. The FASEB Journal. 2021;35(S1). doi:10.1096/fasebj.2021.35.S1.04538

110. Gowda DC, Glushka J, van Halbeek H, Thotakura RN, Bredehorst R, Vogel C-W. N-linked oligosaccharides of cobra venom factor contain novel α (1-3) galactosylated Lex structures. Glycobiology. 2001;11(3):195-208.

111. Ramasamy R. Mosquito vector proteins homologous to α1-3 galactosyl transferases of tick vectors in the context of protective immunity against malaria and hypersensitivity to vector bites. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14(1):303.

112. Fukunaga T, Tanaka N, Furumoto T, et al. Substrate specificities of α1,2- and α1,3-galactosyltransferases and characterization of Gmh1p and Otg1p in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Glycobiology. Published online April 28, 2021. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwab028

113. van Nunen, S. Mammalian Meat Allergy after Tick Bite and Tick Anaphylaxis in Australia. International Tick Symposium (2018). 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C4fzZO9UlzE&list=LLcoL9fUr713IGKBwo-CELVw&index=21 @1:09:00

114. Scott Commins, MD, PhD, personal communication

115. Perusko M, Apostolovic D, Kiewiet MB, Grundström J, Hamsten C, Starkhammar M, Cirkovic Velickovic T, van Hage M. Bovine γ‐globulin, lactoferrin, and lactoperoxidase are relevant bovine milk allergens in patients with α‐Gal syndrome. Allergy. 2021 May 3.

116. Croglio MP, Commins SP, McGill SK. Isolated Gastrointestinal Alpha-gal Meat Allergy Is a Cause for Gastrointestinal Distress Without Anaphylaxis. Gastroenterology. 2021 May 1;160(6):2178-80.

117. Richards NE, Richards Jr RD. Alpha-Gal Allergy as a Cause of Intestinal Symptoms in a Gastroenterology Community Practice. Southern Medical Journal. 2021 Mar 1;114(3):169-73.

118.. Commins SP, James HR, Stevens W, Pochan SL, Land MH, King C, Mozzicato S, Platts-Mills TA. Delayed clinical and ex vivo response to mammalian meat in patients with IgE to galactose-alpha-1, 3-galactose. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2014 Jul 1;134(1):108-15.

119. Wilson JM, Schuyler AJ, Workman L, Gupta M, James HR, Posthumus J, McGowan EC, Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA. Investigation into the α-gal syndrome: characteristics of 261 children and adults reporting red meat allergy. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2019 Sep 1;7(7):2348-58.

120. Ruland KL, Kirzhner M. ENDURAGen graft durability in α-Gal disease. American Journal of Ophthalmology Case Reports. 2022;27:101637.

121. Nourian MM, Stone CA Jr, Siegrist KK, Riess ML. Perioperative implications of patients with alpha gal allergies. J Clin Anesth. 2023;86:111056.

122. Hils M, Hoffard N, Iuliano C, et al. IgE and anaphylaxis specific to the carbohydrate alpha-gal depend on interleukin-4. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Published online December 21, 2023. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2023.12.003

123. Jensen L, Ushinsky A. Management of acute hemorrhage without the use of mammalian products in a patient with alpha-gal syndrome. J Vasc Interv Radiol. Published online May 2, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2024.04.019

124. Wu J, Chen Y, Liu X, Liu S, Deng L, Tang K. Human acellular amniotic membrane/polycaprolactone vascular grafts prepared by electrospinning enable vascular remodeling in vivo. Biomed Eng Online. 2024;23(1):112.

125. Campbell S, Wall L. INTRAOPERATIVE ANAPHYLAXIS TO RABBIT ANTI-THYMOCYTE GLOBULIN. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2024 Nov 1;133(6):S115.

126. Richards N, Wilson J, Platts-Mills T, Richards R. A Retrospective Review of Alpha-gal Syndrome Complicating the Management of Suspected Pancreatic Exocrine Insufficiency in One Gastroenterology Clinic in Central Virginia. Frontiers in Gastroenterology. 2023;2. doi:10.3389/fgstr.2023.1162109

127. Stone CA Jr, Choudhary S, Patterson MF, et al. Tolerance of porcine pancreatic enzymes despite positive skin testing in alpha-gal allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(5):1728-1732.e1.

128. Wilson J, Platts-Mills T, Richards R. S68 Alpha-Gal Syndrome Complicating the Management of Suspected Pancreatic Exocrine Insufficiency. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG. 2022;117(10S):e49.

All the information on alphagalinformation.org is provided in good faith, but we, the creators and authors of the Alpha-gal Information website offer no representation or warranty, explicit or implied, of the accuracy, adequacy, validity, reliability, availability, or completeness of any information on this site. Under no circumstances should we have any liability for any loss or damage incurred by you as a result of relying on information provided here. We are not physicians or medical professionals, researchers, or experts of any kind. Information provided in this website may contain errors and should be confirmed by a physician. Information provided here is not medical advice. It should not be relied upon for decisions about diagnosis, treatment, diet, food choice, nutrition, or any other health or medical decisions. For advice about health or medical decisions including, but not limited to, diagnosis, treatment, diet, and health care consult a physician.

READ FULL DISCLAIMER>